MODELLING THE BUSINESS DYNAMICS OF SURVEYING PRACTICES USING THE SURVSIM SIMULATIONDr Tom KENNIE and Chris WARD, United KingdomKey words: Business management, practice management, IT simulations, profitability. AbstractThe paper focuses on the importance of management development for senior personnel in surveying organisations. The paper introduces a set of Practice Management Guidelines which have been developed for the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS). In addition, the paper introduces the application of a novel computer based business simulation to assist senior managers, in a number of surveying practices, to better understand the factors which influence the commercial success of their businesses. The software enables senior managers to experiment and test out a range of alternative commercial scenarios by modelling the financial (and other) consequences of their decisions. The paper outlines the design of the model and also illustrates how the simulation has been used to help senior managers. In particular, the paper examines, using a number of case studies, how the simulation has been of benefit in a number of alternative formats including;

The paper concludes by emphasising the growing need for senior managers in surveying practices, and increasingly, in government departments, to develop their skills in commercial leadership. 1. INTRODUCTIONFor some surveyors the move into a management position (in either a private or public sector organisation) can be an unsettling and frustrating experience. Gone are the old certainties associated with advising clients on professional matters. In come the new challenges of dealing with increased levels of ambiguity, with fewer absolute rules to follow and even fewer 'cast iron' guaranteed solutions to management and business dilemmas. Confronted with these circumstances the approach of many is to seek certainty - solutions which will work. As consultants we are regularly asked to 'just tell us what to do' usually associated with 'and by the way we don't need any of that theory stuff - just keep it simple'. This paper examines some of our approaches to helping equip surveyors to deal with the transition into the messy world of management - without falling into the trap of seeking simplistic (and often inappropriate) solutions. To do so we will introduce a set of 'Practice Management Guidelines' - a set of key questions for those responsible for managing professional practices. We will also introduce the Practice Development Toolkit - a series of tools designed to help practitioners to undertake a health-check of their firm. The paper concludes by considering the applications of SURVSIM - a computer based simulation of a surveying firm. 2. SOME DIFFICULTIES WITH BUSINESS/MANAGEMENT 'SOLUTIONS'Solutions to business and management problems clearly exist. Libraries of books have been written on the 'solutions'. Guru reputations have been made on the back of these 'solutions'. Many consultancies have 'surfed in' on waves of the latest 'fad solutions'. So what is the problem? Well so often, whilst the solution works - it works only in the particular circumstances which were perceived by someone writing about it after the event. In that sense these 'magic bullet solutions' can be flawed in several ways;

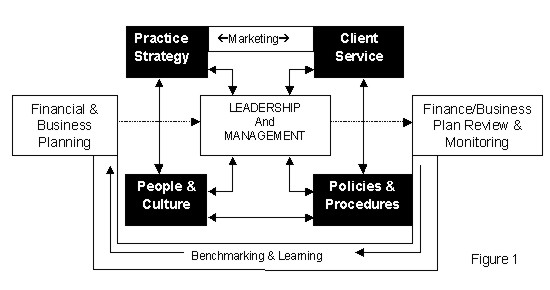

3. AN ALTERNATIVE APPROACHOne of the current themes in the management literature is the idea of 'best practice'. Identify it, copy it/adapt it and implement it and, so the prevailing view seems to suggest, nirvana will follow. But is the concept of 'best practice' sensible? Of course, 'very bad I don't believe what I have just seen practice' exists so perhaps 'better or good practice' might also exist - but 'best' ? This dilemma was one which we faced after winning, in conjunction with the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS), a UK Department for Trade and Industry (DTI) 'Skills Challenge' award. The DTI funded a project to identify 'best practice' in the management of small to medium sized professional practices. The work was initially undertaken with 12 Managing Partners of firms of chartered surveyors, although subsequently the outcomes have proved to be transferable across the professional service sector (and more recently into public sector organisations employing professionals). Our challenge was to project manage a process which would synthesise 'best practice' and capture this for further dissemination. Our initial approach involved a review of current definitions of 'best practice' in the field. In the process we uncovered several very useful frameworks. These ranged from the UK 'Investors in People' standards, the National Vocational Qualification standards for owner managed businesses and customer service, the European Foundation for Quality Management (EFQM) model of quality, the US Baldridge award framework for business excellence and the International Standards Organisation (ISO) 9000 series of quality management systems. In addition we also uncovered several frameworks designed more specifically for the professions, including the Institute for Chartered Accountants In England and Wales (ICAEW) Practice Management Aims, the Surveying Society's Practice Management Standards. All contributed to our thinking - particularly those which approached the issue from a self-assessment 'diagnostic' viewpoint, rather than from a more prescriptive 'do this' standpoint. Out of this initial work with our collaborating partners we devised our own framework. Our aim was not to replicate what had already been produced. Intuitively we all recognised at the time that 'prescription', for all the reasons already mentioned, had its limitation. Our alternative approach focused around the identification of the key management challenges faced by the Managing Partners with whom we were working. From this we wished to uncover the critical questions which would help new partners/managing partners to better understand the nature of management in a professional practice. 4. THE RICS PRACTICE MANAGEMENT GUIDELINES FRAMEWORKThe framework we eventually used to synthesise the various strands of thinking identified by our partners is illustrated in Figure 1. The model illustrates the inter-linking between the various aspects of the process of managing either an entire practice or a business unit within a larger firm.

For each element of the model we worked to identify the most critical questions which the Managing Partners (and our own experience) as practitioners, managers, consultants and academics felt were of most relevance. The complete set of questions became a set of guidelines that have subsequently been published by the RICS (Kennie and Price, 1997). Details on how to obtain the full publication are provided in the references. To illustrate the approach the following text is taken from the section concerned with leadership and culture. 4.1 Leadership and Culture'Professional Practices employ independent professionals: people who may even be more skilled in certain aspects of the job than those who 'manage' them. To lead such people it is not enough to simply be in charge, or to be 'the final expert' whose job is essentially professional quality control. Managers of professionals may perform both function but they also have to inspire, or incentivise, or cajole, or ........ these independent professionals to work together to achieve a common purpose. It is, as others have said before, like herding cats. This guideline has seven elements. First is self-awareness and personal development. The leader who is aware of, and able to make allowance for, his or her own personal attributes is more likely to be able to accomplish the second element, understanding others and building effective relationships. Without such understanding it is unlikely that the leader can provide either a shared sense of purpose or develop a set of reward systems that lead to the achievement of the overall purpose. Reviewing performance objectively requires clear objectives. Self and peer understanding are also the foundation for understanding the 'informal' myriad of subtle interactions which can govern many aspects of behaviour within the practice. A further characteristic of practice leaders is, we suggest, the ability to develop others and above all to stimulate change; to keep the practice responsive to its changing environment. Some Critical Questions 4.1.1 How well do you know and develop yourself?

4.1.2 How clearly do you understand others and the process of building effective business relationships?

4.1.3 What shared 'sense of direction' do you provide?

4.1.4 What formal and informal performance review and reward systems exist?

4.1.5 Do you understand the 'culture' and 'unwritten' rules of the practice?

4.1.6 What amount of time and effort do you spend on the development of others?

4.1.7 How well do you stimulate changes to aspect of the practice's operation?

A similar set of questions exist for each of the other elements of the Practice Management Guidelines framework. 5. THE PRACTICE DEVELOPMENT TOOLKITFollowing the creation of the Practice Management Guidelines a series self-assessment questionnaires have been designed to help Managing Partners undertake a health-check on different aspects of their firm. In some cases this also enables the firm to benchmark its performance against other professional service firms. This 'Practice Development Toolkit' enables partners to evaluate 12 different aspects of its operations. For illustration to take two examples, the toolkit could enable partners to consider;

The use of these diagnostic processes, supported by an experienced facilitator can be of considerable value in helping add structure to a partners retreat or conference. By conducting a more rigorous analysis of the business issues they are facing the Toolkit can also help partners avoid the use of inappropriate solutions identified at the beginning of this paper. 6. SURVSIM - IT BASED SIMULATIONS OF SURVEYING FIRMSThe second tool we have developed is a computer based simulation which enables us to create tailored models which represent the characteristics of any surveying firm. In this section of the paper we develop the argument in favour of using this approach and provide some illustrative examples of how the use of business simulations can be of real, practical value to surveying firms. 6.1 The ChallengeSuppose that, after years as a practitioner, a partner is asked to take a management role within the business. Suddenly, a skills base is needed with features far beyond that which years of professional practice will have developed. So what extra skills does the practitioner need? First and foremost, the ability to understand the firm in a wider context. In one sense to see the firm as an organism; to understand all the factors and triggers which decide its shape, culture and performance. To be able to take the long view, yet retain flexibility as short and medium time scale issues evolve into new forms. To be able to understand the firms relationship with its external world. This is the skill of overview, strategic vision, the understanding of context and how one variable affects the others. Sometimes called 'helicopter vision', it is often hard to acquire. A surveyor whose vision has been confined to a narrow specialism and short assignment planning horizon faces a considerable challenge of mental realignment. There is also a need to understand finance and the manipulation of figures. This requires fluency in the numeric language, which is the lifeblood of any business. The concepts are easy to learn and are mainly common sense. Yet, many professionals believe they have a mental block, which acts against their acquisition of these skills. True understanding of numbers involves the ability to quickly relate sets of numeric data; to spot variances, to interpolate; to understand what they represent and the likely impact elsewhere. A range of other skills will be needed, according to the management responsibility that our practitioner has taken on. These might be with in the area of people management, client handling, marketing, planning and systems work. Some of these may be skills that have already been at least partially developed during professional practice. 6.2 The Skills Development ChallengeHow can partners be encouraged to develop helicopter vision and financial understanding? What can combat the relative narrowness and short-termism of professional practice? Actually managing their own business, preferably sitting alongside experienced and able coaches, is the best method. Mistakes made while learning may, however, adversely affect the firm; but hopefully those in a supportive role can minimise the worst disasters. More difficult, is enabling the periodic review of the effects of decision making on all aspects of the business. Appropriate 'off-site' training, such as exposure to Business School methodology can help. Finding a programme which strongly relates to professional service firms can be something of a challenge. However, the business school approaches of case studies, discussion with other professionals and functional specialist, plus lectures by academics with real business experience can kick-start the development of business holism. SURVSIM combines the best features of both these methods by creating a highly realistic simulation containing all of the characteristics of a real business whilst at the same time enabling those participating to be coached by experienced management development specialists. 6.3 How Can IT Based Business Simulations Assist?Most people learn best by doing. A good business simulation gets people to run what is apparently a real business. Not only do they learn how to analyse business information and make consequent decisions; they can try out strategies which would be too risky to try for real. Simulations can enable people to play the game of running their own business. If the simulation is closely analogous to their current or past experience and accurately represents the culture and operating environment of that business, then their learning can be particularly fast and their absorption and concentration very high. Well constructed simulations can also enable the development of 'helicopter vision'; the ability to fully understand a business as an organic entity. Decisions made in one aspect of the simulated business will impact on other areas as they would in the real business. But how close can we get to the real business? Users require that simulations simulate! In other words, they are most likely to accept and involve themselves in a simulation, which creates a close analogy with their working environment. Providing simulation-based training where the tool replicates an industry other than that of the participants is normally not particularly successful. People are quick to reject that which is off the point, of low relevancy or simple flawed in its design. On the other hand a model which embraces many of the day to day business challenges facing practitioners can be a highly effective means of engaging partners (and others) in management issues. 6.4 SURVSIM and its ApplicationsSURVSIM is a PC based software tool, which enables the simulation of a business. If users wish, and if representative figures are available, SURVSIM can either be used to replicate the financial characteristics of an entire practice, a single department or practice group or alternatively it can be used to build an analogue of a practice. SURVSIM can be used in several different ways:

6.4.1 SURVSIM- Complex Case Study A typical, recent application, of the use of SURVSIM has involved a project to develop the business skills of the key partners within a major international surveying firm. Supported by a detailed case study SURVSIM has been used to emulate the following decision making areas:

The process of using SURVSIM involved the partners attending an intensive two day workshop during the course of which they ran a simulation of their own firm for a period of 12 months. Working in teams which represented the Management Board of the fictitious firm each partner was required to coordinate a different aspect of the firms approach to management (e.g. Business Development, HR, IT, etc.). This had the added advantage of encouraging team working and the opportunity to consider the impact of team working on business success. Since each team was effectively competing with the other for business a degree of healthy competition existed - which had the added impact of deepening the participation of the partners. Each group worked with PC-based performance reports, paper briefings, realistic bid situations, and an in-tray of issues which reflected many of the operational and strategic problems which can arise during a year in the life of a firm. These generic issues can also be supplemented by other matters which from discussions with a particular client it is agreed are worthy of inclusion in the simulation. In so doing the realism of the simulation can be heightened. Over the course of the modelled year, the case study evolved as an external world changed, and their own decisions changed the shape of their firm. Realistic 'mini-case studies' enabled decisions to be made in 'non-financial' areas, such as those of marketing and people management. As the simulation progressed the decisions made by each group were reviewed and the key lessons learnt identified. Tutor input sessions were also an integral part of the workshop and ensured that participants gained a detailed understanding of why certain decisions led to a particular outcome. A final session, involving the presentation of each firms strategy and decisions made provided a further reinforcement of the lessons learnt and there translation to the real world. 6.4.2 Case Study - Outcomes The partners were all very enthusiastic as to the value of the programme they had participated in. All agreed that the process went well beyond the boundaries of a conventional training event. The event created an opportunity for them to review the practice and perform numerous 'what-if' tests to assess the effect of different decisions on business performance, all in the safe environment of the simulation. Their skills in holistically linking the financial and non-financial variables of the firm were also much improved. In addition they achieved a far more detailed understanding of practice finance and the real impact of different pricing and structural issues on financial performance. Their confidence in each other, their operation as a team and their ability to communicate were also enhanced. Finally the connections with their own firm were considered to be very close. The project concluded by the creation of a monthly 'Development Forum' to enable the partners to continue to discuss many of the issues raised during the programme. Further one to one coaching sessions have also been arranged to create more detailed simulations of each practice group, enabling the translation of the concepts from the programme to be implemented in practice. 6.5 Post-Graduate AccreditationA more recent development involving the use of SURVSIM has been the development of post-graduate accreditation where the programme is used as part of a wider development process. To complement the simulation, a comprehensive study guide has been written by the authors. This document and the simulation is currently in the process of being re-structured for delivery through the use of CD-ROM and web-based technologies. 7. CONCLUSIONSIn this paper we have argued that managing a modern professional practice is not about applying imported solutions - solutions which have their origins in the wider world of corporate business. We suggest that the identification of some of the key questions facing a firm and its individual partners is essential. To help, we have provided a brief outline of three sources of potential assistance A set of Practice Management Guidelines; a toolkit for conducting a health-check on the performance of your practice and a computer based simulation to help demonstrate the impact of different business decisions on the performance of a firm. Rather than focus on 'best practice' we believe that more attention needs to be given to 'better' practice but more importantly to 'better process' - the means by which any 'better/best' practice can be implemented- but perhaps that is the subject of another paper… REFERENCESKennie TJM and Price I. 1997. Practice Management Guidelines - Key Questions for the Leaders and Managers of Modern Professional Practices, 43pp. Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors. Copies of the guidelines are available at a cost of £9.50 from RICS Books, Surveyor Court, Westwood Way, Coventry CV4 8JE, Tel: 0171 222 7000 Fax : 0171 334 3851. BIOGRAPHICAL NOTEDr Tom Kennie, MBA is a Director of the Ranmore Consulting Group. He is also a part-time Professor of Practice Management at Sheffield Hallam University. His consulting and management development activities involve working with a range of surveying firms and other professional service firms in the property and management consultancy sectors. Tom originally qualified as a chartered surveyor and has also been HR Director for a major international property advisory practice. He is a Vice President of the International Federation of Surveyors (FIG). Chris Ward, MBA is also a Director of the Ranmore Consulting Group. He has over 15 years experience of working with surveying firms on a wide range of surveying firm management issues. He has a particular interest in financial management and has developed a number of computer based tools to help practitioners understand practice finance. Chris has a background in business management and has also been responsible for training and development activities for a major firm of chartered accountants. CONTACTDr Tom Kennie and Chris Ward 17 April 2001 This page is maintained by the FIG Office. Last revised on 15-03-16. |